Mannerism: The Art of Elegance and Complexity Beyond the Renaissance

The idealized beauty of Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci, as well as balanced compositions and harmonic proportions, are frequently what come to mind when we think of the period. However, what happened next? Between the splendor of the Baroque and the perfection of the High Renaissance, there existed a time that purposefully disobeyed convention: Mannerism.

The intriguing and nuanced movement of Mannerism, which embraced artifice, tension, and intellectual play, is frequently eclipsed by its predecessor and successor. It signaled the transition from early 1500s naturalism to a new kind of artistic expression characterized by ambiguity, intricacy, and stylization.

Time Frame: about 1520–1600

Italy (Florence, Rome) with a regional focus that extends to France, Spain, and the Netherlands

Mannerism began to take shape about 1520, the year Raphael passed away. Many people considered the High Renaissance to have already reached the highest level of artistic accomplishment. In reaction, a newer generation of artists tried to set themselves apart by straying from traditional conventions and investigating more creative, expressive methods of creating art.

The Italian word maniera, which means "style" or "manner," is where the name "Mannerism" originates. In the beginning, it was used to characterize a sophisticated, courtly grace. It later assumed a more critical tone as art historians of the 17th century perceived Mannerism as unduly stylized and manufactured. Nonetheless, contemporary study recognizes the intricacy and inventiveness of the movement.

Major Mannerist Artists and Works

"Deposition from the Cross" (1528)

Da Pontormo, Jacopo (1494–1557)

He is renowned for his vivid, unearthly hues and emotionally charged figures.

"Deposition from the Cross" (1528) is a famous piece. A composition that swirls, with no obvious focal point and weightless, ethereal figures.

"Descent from the Cross" (1521)

Known for his dramatic, almost fantastical scenes, Rosso Fiorentino was a Florentine painter who lived from 1495 until 1540.

"Descent from the Cross" (1521) is a well-known piece that depicts the tumultuous and twisted withdrawal of Christ from the cross.

"Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror"

The classic Mannerist Parmigianino (1503–1540) was known for his grace and length.

renowned piece: "Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror"—a technological wonder demonstrating self-awareness and distortion.

"Allegory with Venus and Cupid"

The Medici's court painter, Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572), was renowned for his sophisticated, cool manner and thought-provoking subjects.

Well-known piece: "Allegory with Venus and Cupid"—a sophisticated, sensual allegory brimming with ambiguity and symbolism.

"The Burial of the Count of Orgaz"

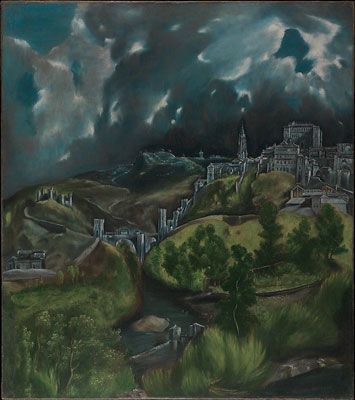

The Greeks (1541-1614)

The expressive style of El Greco, despite being later and geographically distant, shares many characteristics with Mannerism, including elongated shapes, spiritual intensity, and dramatic lighting.

An iconic piece of art: "The Burial of the Count of Orgaz"

Architecture and Sculpture Mannerism

Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne, Rome, by Baldassarre Peruzzi, c. 1535.

Additionally, Mannerism was expressed in sculpture and architecture, where it was humorously disregarded or twisted classical rules.

In order to produce visual suspense and surprise, Giulio Romano purposefully used classical elements in his Palazzo del Te in Mantua in a "incorrect" way. These components included slipping triglyphs and irrational proportions.

The sculpture "Rape of the Sabine Women" (1583) by Giambologna exhibits anatomical perfection and swirling movement in marble.

Among the main traits of Mannerist art are:

1. Exaggerated and extended forms

Unnaturally lengthy, graceful, and contorted into unusual positions are common features of figures. Instead of being accurate, anatomy is altered for dramatic effect.

Using Parmigianino's "Madonna with the Long Neck" as an example, the lengthened neck of the Virgin Mary and the extraordinarily tall infant Christ transcend natural proportions to provide a beautiful, otherworldly look.

2. Complicated Structure and Ambiguity in Space

Mannerist paintings are frequently characterized by cluttered, unbalanced compositions, in contrast to the Renaissance's harmonious symmetry. Intentionally distorted perspective gives the impression that space is condensed or unclear.

3. Color palettes manufactured artificially

Acid greens, frosty blues, and pale pinks were among the distinctive and occasionally startling color schemes that Mannerists preferred to arouse feelings or establish visual tension.

4. Styled elegance and sophistication

Artistic expression prioritizes elegance and refinement above realism. Ornate décor, intricate draperies, and complex stances are common ways to convey this.

5. Themes that are allegorical and intellectual

Complex allegories, esoteric symbolism, or classical mythology are common references in Mannerist painting. The educated elite, who valued cultural allusions and multi-layered meanings, found it appealing.

Legacy and Impact

The emergence of the Baroque in the early 17th century caused Mannerism to lose popularity, although its impact may still be seen in contemporary work that prioritizes intellectualism, emotion, and stylization over realism.

Mannerist tactics have served as a source of inspiration for modern and current artists:

The surrealists were drawn to the twisted figures and dreamy aspects.

The self-referential style and ambiguity of Mannerism are valued by postmodern artists.

Mannerism serves as a reminder that perfection is not necessarily the source of beauty. It can occasionally be found in the sublime, the stylized, and the odd.

View of Toledo

In conclusion,

Neither constrained by the ideals of the High Renaissance nor yet engulfed in the opulence of the Baroque, Mannerism marks a daring and pivotal period in art history. It is a refined dance with shape and meaning, the art of graceful resistance. Although it is frequently misinterpreted, it should be acknowledged as an essential manifestation of the conflicts and changes of its day.

Regardless of your interest in art history or your general appreciation of the unique, Mannerism challenges you to examine more closely and consider not just what is painted but also how and why it is painted in that particular way.